1628,Tygyn Darkhan

Tygyn's grandfather was Badzhey, a rich and powerful Toyon, chief of the Sakha Kangalas clan, with many cattle, horses, warriors, servants and slaves, who lived on the hill near Lake Saysara (near present-day Yakutsk). He had two sons, Munn'an-darkhan and Mod'ogor - both wealthy men. Munn'an-darkhan had two sons - Tygyn and Usun-Oyuun. They lived in the same place, which had once been the territory of the Tungus (Evenk), who still lived there among the Yakuts (Sakha).

About 150,000 Sakha people lived in the region. They were divided into nine ulus (tribes) and each tribe into several clans or families.

Tygyn became a legendary hero and the subject of many tales. He succeeded his father as Toyon-usa - that is the Chief Toyon or King - over all the other Sakha tribes and clans, uniting them into one nation. He reinforced his position by wars with other Sakha tribes and with tribes of other nationals in the region such as Tungus, and the aboriginal inhabitants. Although every Sakha was happy with Tygyn's rule or the supremacy of of the Kangalas clan. Tygyn emerged from each battle triumphant and even wealthier.

Tygyn owned farmsteads and estates around Lake Saysara, at Ytyk-Kll, Yuryun-Kll, and near Kytaanakh-Kyrdal. His horses and cattle, his family and clans people, warriors, slaves and hired hands lived here. He had an empire to pass on to his sons and grandsons. Tygyn's sons were: Bedzheke, Ökrey and Challayy. Bedzheke's son was Masary Bozekuyev.

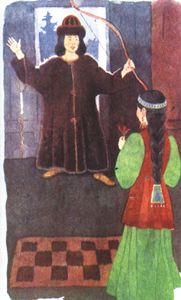

In 1628, just as Tygyn might have thought his heroic days over and he could enjoy a quiet old age, a new enemy arrived - the Russians. But not as shown in this painting in the museum at Tiksi. They were far from friendly and were not welcomed.

In 1628, just as Tygyn might have thought his heroic days over and he could enjoy a quiet old age, a new enemy arrived - the Russians. But not as shown in this painting in the museum at Tiksi. They were far from friendly and were not welcomed.

A group of Russian mercenaries and freebooters under their Cossack leader Vassily Bugor arrived at the Lena in 1628. They had travelled on skis from the Yenesey, after hearing tales from the Tungus of another great river, on the other side of which lived people who travelled on the river in boats, had horses, wore armour and (this was the real lure) mined gold and silver. The Russians were followed by more, all with guns.

Tygyn could raise 500 heavily armoured warriors on horseback but his weaponry was out-of- date. The Russians had guns. They also gained the support of an opponent of Tygyn - Millach the toyon of a small tribe which had separated from the Kangalas and lived on a hill not very far away, on the eastern shores of the Lena, a place called Tshebedal. Millach supplied the Russians with food, and gave them forty archers to help defeat Tygyn and the Kangalas.

The mediaeval Sakha warriors had never faced guns before. They were overcome, and the Russians captured Tygyn and held him imprisoned as a hostage. Tygyn was by then very aged and suffering from a malignant skin disease and senility. Being imprisoned in grim conditions did not help. In 1634, Tygyn died. His son Bedzheke was captured by the Russians to be a hostage in his place. Another son, Ökrey succeeded as Toyon-usa.

Tygyn was to remain a legendary national hero to the Sakha people and Russian historians were expected to destroy such an image not support it, if they wanted their books published.

1630-1640 Russians demand yasak

In 1630, the Russians started demanding yasak (tribute or protection money), from the local Sakha. In 1632, they built a wooden fortress (ostrog) at Tshebedal, home of their ally Millach. His tribe was called by the Russians Namski Ulus (Our Tribe).

In 1632, the Russians were reinforced by more Cossacks from Yeniseysk. They built another wooden fortress on the land of the Kangalas clan. They first called this Lensk, but it was renamed Yakutsk, as they called the Sakha Yakut, and became the capital city of the new Russian Yakutia.

The Kangalas were not going to give up their country to the Russians willingly. They combined with neighbouring clans under the Toyon Mymak, and raised a force which attacked the Russian fort, intending to destroy it, and drive the Russians out of their country. They were beaten by the Russian guns.

Meanwhile more Russians were coming into the country. They explored the country and travelled up the Lena. In 1632, Cossacks built a fort at a Sakha settlement by the Lena (just above the arctic circle) which they called Zhigansk.

Meanwhile more Russians were coming into the country. They explored the country and travelled up the Lena. In 1632, Cossacks built a fort at a Sakha settlement by the Lena (just above the arctic circle) which they called Zhigansk.

In 1633, the Russians had sailed right up to the Lena delta and were demanding tribute from all the local people. To back up their extortions they built more forts. They needed them as their demands for tribute were not welcome. The Russians assisted their collections of loot, with threats, savage violence and by seizing hostages which were imprisoned in dire conditions in the forts.

Officially the tribute was a taxation imposed by and to be paid to the Tsar and his government. In reality - miles away from Moscow, it was every man for himself, and they extorted what they could for themselves. They would say "The Tsar is a long way away, and God is very high above". Frequently more than one band of Cossacks was demanding tribute from the same people. The bands of Cossacks also fought each other. It is not surprising that the Sakha and Tungus words for a Russian also meant a bandit.

In 1634, the Cossack ataman (leader) Ivan Galkin, wrote in his report for the government, "the Kangalas princes are numerous and possess the whole earth, and many princes fear them". His reason for these over the top words was fear. Tygyn had just died while he was a hostage under his responsibility. Galkin knew his sons and relatives were out for revenge. He needed more troops.

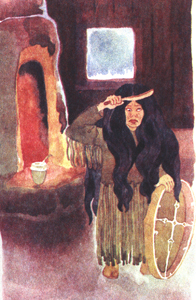

Tygyn's sons Challayy and Bedzheke turned for advice to a great udagan (shamaness). Her name was Taalay, and she lived by lake Taly near Yakutsk. When Taalay saw the princes coming to see her, she transformed herself into a tower of flame. When they pleaded for help, she agreed to hold a ceremony and prophesize for them. Afterwards she told them "The runaways have already sailed to the headwaters of the river. Sitting in the clouds I saw them cutting logs with wide axes." In 1636, the Kangalas and Betan clans again besieged the Russian fort at Yakutsk, but were again defeated. The Russians could call up limitless forces.

1640-1646 - Golovin

In 1638 The first Russian Governor of Yakutsk was appointed in Moscow. This was Peter Golovin. To aid him with the organization of the new Russian province, and also to keep an eye on what he was doing he was accompanied by an assistant Gliyebov and by a priest Efim Filatov. He was also to be escorted by a large army of streltsy (musketeers) and Cossacks as well as officials, traders and hangers-on.

The army was needed by the Russians, as by the time Golovin had arranged in Yakutsk on 6th June 1640, the Yakuts had made another attempt to fight the Russians and drive them out of their country.

Golovin's first task was to subdue the Yakuts and he proceeded to do so as savagely as possible. He then imposed heavy, but unspecified, taxes on the local population. The motivation was greed and sadism. He organised the capture and torture of people for not paying all their taxes to him - but he never actually specified the amount they had to pay.

Not surprisingly, the Yakuts organised an attack on their Russian oppressors in 1641. In 1642 they attacked Yakutsk. They were defeated, but Tygyn's sons had the satisfaction of killing Galkin, in revenge for the suffering and death of their father when he was in Galkin's hands.

Golovin was determined to exterminate the Yakuts. Their defeat had been difficult, and to subdue them, he ordered terrible reprisals. Yakut "rebels" had their noses and ears cut off and their eyes put out. Alternatively they were buried alive in the ground up to the eyes.

Golovin can not be accused of racism for he was just as nasty to the Russians under his command. Not exactly weedy types from a sheltered life, they still found Golovin too sadistic to tolerate. They complained to Golovin's fellow officials that Golovin "beat us mercilessly with the knout, pulled our limbs out of joint, poured ice water over our heads, pulled at our veins and navels with hot pliers, scattered hot ashes on our backs, and drove needles under our finger nails". And that was just to impose routine discipline on his troops.

In the wooden prison at Yakutsk the torturers and the executioners were said to hard at work from dawn to dusk (which is continuously in mid-summer).

Golovin's fellow officials heard the complaints sympathetically, for they had their own grudges against Golovin. He was taking far more than his fair share of the tribute extorted from the native population.

Gliyebov collected all the evidence he could about Golovin and sent a fat letter to Moscow complaining about Golovin's behaviour. It took months for communications to reach Moscow from Yakutsk. A government secretary, Soushelef, was sent out to Yakutsk in 1645 to investigate the allegations against Golovin. He collected a list of complaints about Golovin's administration that were to fill two large bound manuscript volumes weighing about 100 pounds each.

The following year, in 1646, Golovin was sacked. Armed guards brought the news of his career change and took him back to Tobolsk - which was the centre for the government of Siberia. Here he was imprisoned and tortured on the rack and with the knout. A lot of people must have been pleased to hear about this.

1648, Dezhnev

Semen Ivanovich Dezhnev was born sometime about 1605 and somewhere in the north of Russia. Around 1630 he entered military service as a Cossack and was sent to the garrison at Tobolsk, and then posted to Yakutsk. He was one of the yasak collectors on the rivers Lena, Yana and Indigirka. In the 1640s he was on the Kolyma river with Mikhail Stadukhin and others trying to collect yasak from the Yukaghirs. The Yukaghirs resisted the cruel and savage attempts of the Cossacks to extract as much from them as they could. Dezhnev was twice wounded in the fighting.

From the mouth of the Kolyma, a group of traders and Cossacks led by Isaya Ignatiyev sailed east in 1646, along the coast as far as Chaunskaya guba, where they traded for a cargo of walrus ivory from the Chukchi and brought it back to the Kolyma. News of this as well as the prospect of a new source of valuable furs, led to a new Russian expedition planned by a trader called Fedot Alekseyev. He was from Kholmogory where the British and other foreign merchants had their offices, near the mouth of the River Dvina. Alekseyev was an agent for wealthy Moscow merchant Alexei Usov. Alekseyev needed a military escort for his expedition and was allocated the services of the Cossack Dezhnev.

They planned to set out from the mouth of the Kolyma in 1647, but were defeated by ice, right up to the shore. While they waited for more favourable conditions, the expedition expanded as others joined them.

By the time they set off down the Kolyma and out to the Arctic Ocean on 20th June 1648, there were three large groups all together in seven boats. Alekseyev had also acquired a Yakut wife who travelled with him along with thirty other people. Dezhnev was under government orders not only to escort Alekseyev but also to extract yasak from any new local people they met. He was expected to collect 280 sables for the government. He had hired 20 men to work under his orders to accomplish this. The third group of people was led by Cossack Gerasim Ankudinov. They had joined the expedition for their own purposes.

They had set out in the middle of summer when the sky was light all the time, and if they could see the sun it was shining from the north at midnight. But they were unlucky with the weather again. The ice had cleared, but the weather was stormy. The sailing boats became separated.

The three boats carrying Dezhnev, Alekseyev and Ankudinov got as far as the end of the northern coast and had reached what was to be called the Bering Strait. The other four boats had disappeared on the way.

Then Ankudinov's boat sunk in a storm. He and some of his crew were saved. Alekseyev's boat is thought to have made it to Kamchatka where he and his wife and the other survivors continued to live, but this is uncertain. Dezhnev's boat was wrecked, but he and a few of his companions managed to get ashore.

They were discovered on the river Anadyr nearly two years later in 1650 by Mikhail Stadukhin and other Cossacks who had travelled overland. Stadukhin's party had attempted to sail eastwards along the Arctic coast, in 1649, but had been defeated by the ice.

Dezhnev therefore was one of the first Europeans to sail through the Bering Strait, but at the time no one knew this. It was discovered later by Gerhard Müller on the expedition of 1734-9 when he was rummaging in the archives in Yakutsk in August 1736. He found Dezhnev's petitions for arrears of pay.

1649 - 1662

Golovin was not the last of the sadistic psychopathic Russian commanders in Siberia. Russian officials sent out to Siberia tended to be the ones Moscow preferred to have living at a distance. So far from the centre of government, many government representatives felt free to do as they pleased. There were limits. As with Golovin, reports of excessive brutality, violence, graft and mismanagement discredited the Russian state, both within and abroad, which threatened the government and the Tsar. Yakutsk governors tended not remain in their posts long before they were arrested and placed in the care of armed guards.

Many people travelled to Siberia in the hope of a better life. A new start. At the same time people all along the social scale were being sent to Siberia to remove them from Russia. Political dissidents, religious dissenters, prisoners of war, criminals, the poor and the inadequate, were joined by refugees fleeing debts, poverty, other things they had rather leave forgotten, religious nutters, escaped serfs. Siberia was becoming a dumping ground for Russian riffraff much to the dismay of the locals.

In 1649 Yakutia was made a separate administrative district of Siberia with its capital at Yakutsk. The boundaries were extended to Ilimsk so as to included the portage link between the Yenisey and the Lena. The rivers were the arteries for transport in Siberia. Yakutsk had a military governor who was responsible to the Siberian administrative capital of Tobolsk.

By 1662 a regular route was established from the River Lena back to Moscow, with post stations (yam) and more than 3,000 official drivers (yamshchik) working on the route to carry the post and supplies between Yakutsk and Moscow. The journey took as much as two years.

The total Russian population of the whole of Siberia was then about 70,000 of which 20,000 was military troops employed to suppress the native population.

1655-1675 the effect of the Manchu Empire upon Yakutia

At the same time that Tygyn was conquering the tribes of Yakutia, Manchuria, on his south-eastern borders was also expanding once more under its leader Aisin-Gioro Nurhachi.

In 1644, the Manchu occupied Beijing and founded the Qing dynasty which was to be the last Imperial dynasty of China, with Manchurian ruler Aisin-Gioro Fulin as Emperor of China.

The Tungus-Manchurian tribes and clans in Siberia, now could claim the protection of an overlord more powerful in that part of the world than the Russians, with large well equipped armies (Jesuits had helped update their guns) guarding their borders. Sakha and even Cossacks also escaped to Manchurian territory to escape Russian rule.

By 1670 Manchurian sovereignty had been reinstated over the Lamuts (Evens) on the Pacific coast around Okhotsk (Yakutia's east corner). And also collected tribute from Lamut clans on the Maya river who had been subjected to the Russians. Yakuts were encouraged to move south where Manchu armies had cleared out the Russian troops and mercenaries.

The Cossacks were independent mercenaries employed by the Russian government. In 1655 local Cossacks in Yakutia rebelled against the Russian officials at Yakutsk. They banded together and swore an oath to be free of their Russian oppressors.

Having had enough of Yakutia, they planned to emigrate south to a better climate. They raided warehouses in Yakutsk and pirated boats. Some three hundred of them with their (mostly Yakut) wives and children under their ataman Sorokin, set off down the rivers until they reached the Amur region in Manchurian territory where they settled in Albazin.

A Tungus tribe whose leader was called "Petrushka-Olyeni" by the Russians (Reindeer-Pete) escaped from the Lena where they had lived, fighting and killing Cossacks to get away to Dahuria a Manchurian province which Russia claimed.

The Albazin Cossacks found them and extorted tribute from Reindeer Pete of fifty sable skins. Reindeer Pete appealed to Beijing and was supported by Chinese governors in the region as they and others also molested by Albazin were Chinese subjects. Several complaints about the behaviour of Cossacks on the Manchurian frontiers were sent to Beijing. The Russians and Cossacks were called bandits.

Fifty Sakha (Yakut) men (referred to by the Russian ambassador as deserters) escaped from Yakutsk with their wives and children. The governor sent a boyarson with Cossacks in pursuit of them. When they caught up with them, there was a fight. Many of the Cossacks were wounded and the Yakuts escaped. They settled amongst the Birars, a Tungus tribe tributary to the Manchus, but who were also exploited for tribute by Albazin.

Two of the Sakha leaders were taken by Manchu government officials to Beijing to the Emperor's Court. Their clothes were thought unusual, in the "German" fashion. (The traditional Yakut coat did look much like 17th century European dress). The Sakha representatives said that they had been sent by the Yakut princes to the Manchurian Emperor to offer their subjection to their rule, as the Russians oppressed them grievously, exacting tribute beyond their skill to furnish. Officials escorted them back to their companions and new Manchurian home.

The Russian government was furious at these defections by people who found the - not notably tolerant Manchu government still preferable to Russian rule. The threat was immense. The Russian Empire stood to lose most of its eastern territory and with it a possible overland passage to America, access to the Pacific and above all friendly relations and profitable trade with China. They kept a close check on all defectors.

A report in 1670 from the Russian ambassador in Beijing, Milovanov stated "And after that came to the same Embassy compound a traitor, by race a Crim-Tatar Anashka Urusmanov who had belonged to the former voevoda (governor) of the Lena Dmitriev Fransbekov, but had fled from Dahuria from the Amur river into China some years back...And in the Chinese capital they saw a traitor a Russian, who had belonged to the Lena boyarson Thedorov Pushchin, Takhomka by name who had fled from Dahuria from Niki fort Cherigov in former years. And those traitors Anashko and Takhomka have taken wives unto themselves in the Chinese capital; and they follow the Chinese customs and receive food from the Bogdikhan (Manchu Emperor) and they dwell in houses of their own."

The Tsar sent a new ambassador to Beijing, Sparthary. Sparthary's Chinese interpreter was so useless he had him flogged. He then relied on Ferdinand Verbiest, the Jesuit astronomer from what is now Belgium, who in 1670 impressed the young emperor Kangxi, by defeating the Chinese Muslim astronomer Yang Guang Xian who had written a book against the Jesuits, in a challenge held at court.

Sparthary requested that Kangxi hand over the Yakut refugees. But Kangxi refused. The traffic had not been all one way. The Tungus Solon Prince Gantimur had crossed the border into the Russian side. Kangxi refused to hand over the Yakuts except in exchange for Gantimur. It was stalemate.

In a letter to the Tsar, Kangxi also said "Now I am told that the people called Sakha belong to the Russian jurisdiction...but whether truly or not I cannot say." The Yakuts remained in Manchuria but they were not able to persuade the Emperor to send his troops as far north as Yakutsk to help them expel the Russians from their country.

l675-1678

In 1675 on the Viluy, in the Western corner of Yakutia, Russians and Yakuts came to blows over a dispute on hunting grounds for fur animals. In the resulting massive fight, one Cossack and several Russian trappers were killed.

A troop of Russians together with Yakut collaborators was sent out from Yakutsk to arrest and bring back the local Yakut chief Baltuga. Baltuga met them with an armed gang of some fifty Yakuts and Tungus. In the battle that followed, the locals were beaten, and Baltuga was taken prisoner. He was carried back to Yakutsk to be imprisoned and tortured. But he had supporters. A number of Yakut Toyons got together a petition for his pardon. Baltuga was released.

In July 1675, Governor Andrei Barneshlev was sent to Yakutsk. He hated the Russian Religious Dissenters who were exiled here, after their tongues had been cut. He hated political exiles. He hated the Yakut Toyons.

Barneshlev never sat down to a meal without having previously sent someone to capital punishment by a variety of cruel methods, and usually for the most trifling offences. His victims were quartered, impaled, boiled alive in a cauldron, anything new he could think of. However if Barneshlev was in a good humour he ordered hanging as a special favour. Unfortunately he was rarely in a good mood.

On the 3rd July 1678, he was charged for having received bribes, sacked, and sent to Tobolsk.

New Russian laws came into force in 1678 to assist the collection of taxes (really tribute since they gained nothing for these payments). Native chiefs were to be responsible for the taxes of their own people.

Those Yakut Toyons who were collaborating with the Russians, received the status of members of the Russian hereditary aristocracy as princes (or "little-princes"). But for ordinary clan members, the opposite happened. They were reduced to the level of serfs. They had to bear the burden of heavy taxation, while their Toyon who achieved his status as tax collector by bribes to the governor, had the additional privilege of tax exemption.

1682-1684 Priklonsky and Djennik

In 1682 Priklonsky was made Governor of Yakutsk. He faced an armed uprising.

Yakuts were joined by religious dissenters, exiles and some Cossacks - many of whom had Yakut wives. They all had guns by now. Their leader was Djennik, chief of the Kangalas, descendent of Tygyn.

Djennik was wounded in the battle, captured, and taken to Yakutsk. Here he was flayed alive while his wife was in labour nearby. His newly-born child was wrapped in his skin, while the mother was put on the rack.

In l684 an argument between clans developed into an armed uprising against the Russians and those Toyons who collaborated with them. The army of Yakuts and Tungus were led by Orukan and Dachig. The Russian troops had more up to date and better weapons and outnumbered them. The leaders were hanged and quartered.

end of the 17th century

The ancestors of the Kolymian Yakuts were fugitive insurgents, who escaped after their defeat under Djennik, their leader. These people fled to Kolyma - the mountain region to the North West with the world's coldest winters, because they were in deadly fear after the horror of the suppression of the revolt.

The ferocious tortures and executions of that time were kept in remembrance by song and story from one generation to another.

Since 1630 oppression from the Russians caused Evenk clans to migrate from the Angara, Viluy and Lena rivers to the Chinese and borders. This brought them into conflict with other clans, leading to wars between them. A situation exploited by Russian officials. There were frequent Tungus attacks on trappers and yasak collectors. Near the Kotuy, the extortion and cruelty of the Russian garrison at the Lake Yesai outpost provoked the local Tungus to kill them they then fled for the Olenyok and Lena valleys.

The Russian demand for furs had impoverished the native people who were forced to hunt sable etc. to pay taxes, so had less time for collecting and preparing food and clothing and other necessary things they needed to do to survive and to live well. They had to depend on Russian traders for supplies of guns, shot and food like flour, while Russian settlers took their fishing and hunting territories. They were left burdened by debts they were forced to honour as they were constantly cheated in trade by the Russians.

This in addition to pogroms, cruelty and epidemics of diseases new to them, including syphilis, wiped out some tribes completely and seriously depleted others. Leaving the survivors impoverished to the extent of starvation and famine.

The Orthodox Church did not help them. They backed the cruel treatment of pagans, and many of the priests were cruel slave owners. As with the government, the church sent out to Siberia the men they hoped not to see again.

Women suffered the most under Russian rule. Russians captured native women to use as slaves and prostitutes and expected to be provided with women (or boys) when travelling on service. Boys and women were bought and sold.

Men acquiring native wives used to apply to have them baptised as Christians because Christians did not have to pay yasak. Because of this policy the baptism of natives by missionaries was not encouraged by the Russian government as it meant loss of revenue. If a native was baptised then he or she became bound as a serf to the person who effected the conversion. As a result Cossacks tried to force converts who then became their slaves and could be sold by them for cash.

As the taiga was overhunted because of the Russian demand for yasak, and the furs run out, the Russians looked to new ways of exploiting the country. Mines were developed, sometimes on the site of older, Sakha mines. The discovery of useful and valuable mineral wealth meant that Russia would never give up this land easily.

In the 1680s, the sulphur and saltpetre found near Yakutsk provided raw material for a powder mill, part of the developing munitions industry, needed for the exploration and exploitation of Eastern Siberia and the the North Pacific.

The Russian population was expanding fast as peasants and artisans escaped the laws on serfdom and on religion for an arduous long trek on foot into what they thought would be the freedom of Siberia.

By the end of the 17th century, the number of Russian colonists in Siberia was equal to the number of British colonists in North America.

Yakutsk becomes centre for scientific exploration

Yakutsk became the centre of overland military and scientific expeditions to the North Pacific and the Far East of Siberia.

The north coast of Yakutia is blocked by ice most of the year and was cut off from east and west by the pack ice all year.

Attempts to send a ship through the North-East Passage began with the English expedition sponsored by 15 year old King Edward VI and left London in May 1553 two months before he died.

Only one ship, the Edward Bonaventure, under Richard Chancellor, survived the winter as it had landed at the mouth of the River Dvina. The crew was taken to Moscow to meet Tsar Ivan IV, and a joint British-Russian trading company was set up. (The 16th century British Embassy building is near the Hotel Rossia).

Ivan IV was particularly interested in this new route from Europe, as he could be supplied with guns directly by the British, bypassing the nearby countries on the overland route, which were naturally reluctant to supply modern weapons and technology to the large developing and potentially menacing country on their borders.

Ivan IV had just conquered Kazan, to the east of Moscovy. With the supply of British handguns and helped by the more advanced technology of Western Europe, and its engineers, Ivan IV expanded what he had inherited as the Dukedom of Moscovy into the Russian Empire. At the time of his death he was trying to take over the Khanate of Siberia. This was not conquered by the Russians until the end of the 16th century. The capital - Sibir was renamed Tobolsk and became the capital of Russian Siberia.

In 1556 Stephen Burrough sailed the North-East Passage as far as Novaya Zemlya - and described a Samoyed shaman seance in detail. In 1580 Arthur Pet and Charles Jackman got only a little further east.

At the end of the 16th century a Dutch expedition under Barents got as far as Novaya Zemlya. After this date Russia protected its own interests by forbidding foreign expeditions to venture further.

Once upon a time, near Zhigansk, lived a girl called Agrafena. She was very poor, thin and miserable, and lived on her own in a horrible little hut. There was no fire in her hearth and no meat boiling in the pot. Only the local shaman helped her. The shaman was getting old and wanted a successor to inherit his magic powers. Agrafena threw her Christian cross in the Lena, and trained to be a shamaness (utagan).

Once upon a time, near Zhigansk, lived a girl called Agrafena. She was very poor, thin and miserable, and lived on her own in a horrible little hut. There was no fire in her hearth and no meat boiling in the pot. Only the local shaman helped her. The shaman was getting old and wanted a successor to inherit his magic powers. Agrafena threw her Christian cross in the Lena, and trained to be a shamaness (utagan).

One day Agrafena decided to go shopping in Zhigansk.

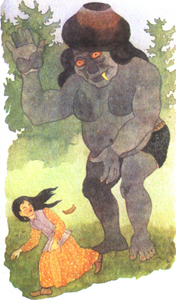

One day Agrafena decided to go shopping in Zhigansk. Later that night Agrafena was awakened by a terrible storm. And a loud rapping at the door. When she opened the door to her horror there was the old dead shaman, risen from his tomb. He was surrounded by horrible evil spirits - abaaci and yor.

Later that night Agrafena was awakened by a terrible storm. And a loud rapping at the door. When she opened the door to her horror there was the old dead shaman, risen from his tomb. He was surrounded by horrible evil spirits - abaaci and yor.